It’s the end of the year. Are you okay?

This is the 12th article in a monthly series from members of the GPs Down Under (GPDU) Facebook group, a not-for-profit GP community-led group with over 6000 members, which is based on GP-led learning, peer support and GP advocacy.

I AM going to talk about dialogue and communication in health care because this sits at the heart of everything we do as health care providers, whether we are talking to patients or to each other.

The Royal Australian College of GPs endorses communication as a necessary discipline and skill for health care providers. We also know that emotional regulation and developing observation skills contribute to patient care. However, managing an intercollegiate professional dialogue between practitioners and patients is not always optimum.

Incivility hurts the workplace, and it hurts relationships. Riskin, in a randomised controlled trial, in which neonatal intensive care unit medical teams participated in a training simulation that exposed them to either rude or neutral comments from an observer, found that procedural performance scores were lower for members of teams exposed to rudeness than to members of the control teams. Rudeness can arise from patients too, as illustrated by the recent social media trending hashtag #doctorsaredickheads. Morgan and Brindley responded in the BMJ to this patient-led charge by pointing out that perhaps doctors were human.

The causes of incivility are complex, no doubt, and range from systemic factors, a high performance workplace, patient angst, the pesky amygdala (remembering all our emotional responses), physician burnout and distress (here). It’s hard to know how to unravel all of that, and likely it is interdependent. So, instead of looking at the endless causes, I am going to suggest four methods of response that can help. I will start with the hardest part, which is the basis of all scientific dialogue, and finish with the last of them, which is the most important.

Method 1: Hegel and the cognitive, intellectual approach

Hegel moved beyond the Socratic tradition of ancient logic in which if any premise was wrong, then the conclusion was always wrong. Socratic dialogue can be seen as a zero-sum game and constitutes the battle of ideas by which our current media climate thrives. The win–lose scenario of “gotcha” moments is enacted vividly in modern discourse.

Hegel countered, however, that two seemingly opposing premises or theses did not necessarily cancel each other out, but could be used to synthesise and progress a new understanding. This, we can see, is the basis of the progression of all science.

In the context of incivility, however, when someone opposes you, perhaps stop and consider how to synthesise the opposition. It’s a cognitive exercise.

So, one strategy when faced with conflict and disagreement is to use Hegelian theory to consider deeply the thesis and the antithesis, and then move to synthesis. This reflection is useful when patients on social media spit globally incriminating statements at the medical profession.

Method 2: David Bohm the physicist and humanising dialogue

David Bohm was a theoretical physicist who expanded upon the nature of dialogue by suggesting that listening includes not only reflecting on our own observations and assumptions but listening carefully within the conversation to where our intent is misunderstood. This is as true for scientific inquiry as for any other human interaction. The goal of listening is not so much waiting to correct a literal so-called fact but a nurturing of a warm, curious attentional stance.

Warmth and fellowship in dialogue is likely to generate great understandings of the nature of existence as well as facilitate the reduction of our fragmented understandings. Using an attentional device of warm curiosity might be helpful in responding to the social media outpouring of frustration with the medical profession. For instance, in the case of the #doctorsaredickheads trend, countering that this is anatomically factually incorrect might not alter the course of dialogue. However, if we were to reflect with curiosity on our own response to the allegation, as well as to the misunderstanding of the intent of altruistic medical practice, this might be more helpful.

Social media is difficult because it increasingly allows the visibility of some political inequality. The contribution to health care dialogue from some patients and even some doctors may not otherwise be easily heard. Warmth, curiosity and a clearly communicated intent to heal could reduce the fragmentation and “othering” of patients with complicated diagnoses, who now have access to social media.

Interestingly, however, doctors responded to the recent collective social media dialogue by talking about their own pain – burnout, work rosters and workload. Doctors described considerable systemic pressures (here, here and here).

This was a new thesis arising: that the workplace is contributing to hurting its workers. The National beyondblue survey published in 2013 suggested that medical professionals’ mental health was at low levels and not consistent with similar tertiary educated professionals.

It seems that in our rush to efficiency in industrialised modern health care, the dialogue around the resultant disempowerment and suffering of both patients and doctors was expressed by #doctorsaredickheads.

How do we address and synthesise the pain and suffering of others? Maybe by adding in the affect and the human, as suggested by Bohm, we can overcome the “collective incoherence”, which he suggested contributed so much to human suffering.

Humanising the system is illustrated by the following anecdote.

One of my medical friends recently had a biopsy of a major organ for cancer and was down-dressed into a backless gown. His face was necessarily covered, he was surrounded by technology and he knew there was an approaching sharp needle. Yet, in among the industrialised process, a health care provider who was unseen, was comforting and patting his hand. He told me this action alone was the one he remembered. While he intellectually understood the need for a deconstructed, reduced self and silent team concentration, he recalled that the humanity of the unseen health care professional had the most impact on him. The touch was human recognition of the need for validation, communication and kindness. It was unspoken and, yet, a dialogue of care. It seems that human touch recognised and validated his presence within the system of diagnosis.

How much harder, however, is the unfamiliar world of health care for patients when the diagnosis is not definite? Particularly for somatised and psychological aspects of illness and those with no name, the so-called heart sinks? These patients have always created great angst in doctors as we search for the name for medically unexplained symptoms. We know, for instance, of the hierarchy of illness prestige, in which some diseases have higher status than others. The low status of some diseases, plus political inequality within an industrialised process, might explain some of the social media voices. The patient voice on social media can angrily denounce a profession that denies the name of their own lived experience of the absence of health. We can, however, begin a dialogue with curiosity regarding wellbeing, rather than the facts of disease, bearing in mind the World Health Organization’s 1948 definition of health:

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

The wellbeing of our patients, our doctors and our system is a synthesised dialogue that could rise above the social media collective incoherence.

As Hegel and Bohm have illustrated, this conversation is not easy, and it has to address the very complex intellectual pursuit of good dialogue. How can we cut across these skills in the often time-pressured and people-pressured interactions within complex health care systems? Few of us will read philosophy.

Method 3: a shortcut to dialogue

There is a third GP-led contribution to consider when opening and maintaining a dialogue, especially as a response to incivility or a win–lose conversation. A wise member of our GPs Down Under group, Dr Genevieve Yates, suggests that when a colleague or patient is difficult, even abusive, obstructionist or derisive of our role in primary care, ask very simply, with a pause:

“Are you okay?”

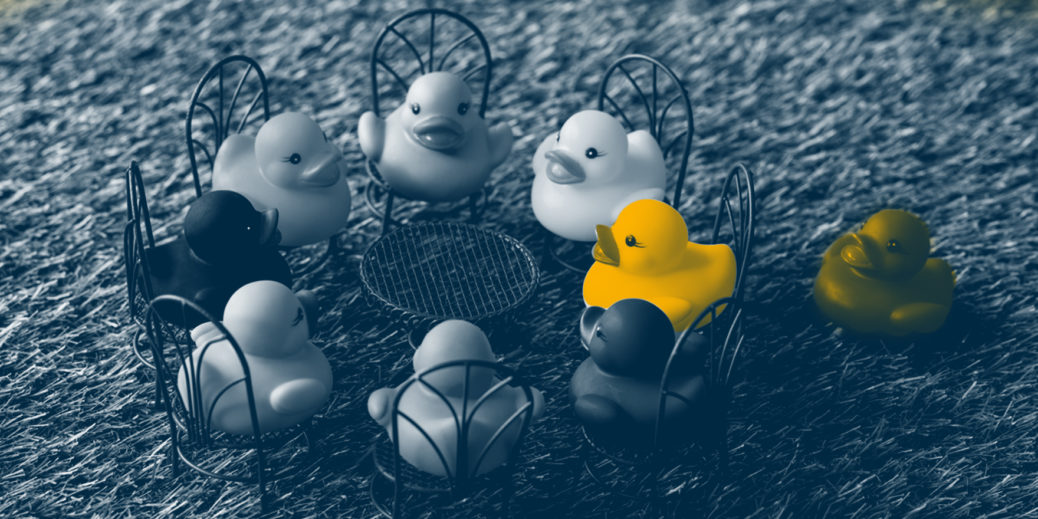

This is a disarming response to an unfortunate interaction between human beings. Arguing the facts is too easily done when tired, when managing uncertainty, when our emotions get in the way or when our status is challenged. The GPs Down Under response is short, swift and can begin a dialogue of “thesis–antithesis–synthesis”. By addressing the affect and the human, we might get a shift from the Socratic win–lose to the Hegelian synthesis so necessary to progress the safety of colleagues, staff and patients.

Method 4: the reflective personal self

The often missing part is to apply these rational principles to ourselves; to create a reflective dialogue within ourselves. Combining the intellect and affect in our conversations within ourselves as well as within the broader health workplace is a worthy aim. This was one of the central arguments of Bohm: attend to our own observations of affective knowledge and assumed personal values. Ask of yourself as a doctor or as a patient: “Am I okay?”

The internal dialogue of our own wellbeing cannot be underestimated. Pause and check in to the intellect, the affect and to wellbeing. To further consider the collective understanding of what health care means requires a greater dialogue than one of numerate efficiency and diagnosis.

What my friend having the biopsy remembered was the patting of his hand – the hand of health care dialogue that said: “I see your suffering; you are significant; you do matter”. Whether it is a patient, or a colleague or a staff member who is emotional, we need to listen carefully and pause. Humanising our health care means more than excelling at processes. It means thinking about concepts of health as per the WHO definition. Both with ourselves and with each other, the conversation about humanising health care is much more than a literal interpretation of contested and often unreliable facts. It is a participatory exercise with philosophy, science and the arts.

Long may that civil and deeply philosophical dialogue continue.

The administration team and the GPs of GPs Down Under wish you a happy holiday season and the gift of caring, thoughtful dialogue at the festive tables of your families, your colleagues, patients and staff.

Dr Karen Price is a GP and a member of the GPs Down Under Facebook group administrative team.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or MJA InSight unless that is so stated.